Not that there’s not some entertainment. No, we get an opening montage with Dad channeling Johnny Cash, complete with wig and hoisted-high guitar. And we get some great pics of the early country and rockabilly artists from the 50s, and we hear clips of Patti Page’s “Tennessee Waltz,” Hank Williams’ “Cold, Cold Heart,” and Eddy Arnold’s “Bouquet of Roses.” And live-in-the-studio guests Glenn Canyon and the Americanyons serve up Kris Kristofferson’s “For the Good Times” alongside an original from the Canyon canon.

But most of what transpires in these 30 minutes feels as it felt when I took Dad’s class back when I attended the University of Cincinnati, including an interesting look at the development of BMI as a competing force with which ASCAP ended up having to reckon and five 1974-era prescient predictions about the future of country music, all of which, to one extent or another, have come true in the near-50 years since.

Please enjoy “Country Music II.”

Not that there’s not some entertainment. No, we get an opening montage with Dad channeling Johnny Cash, complete with wig and hoisted-high guitar. And we get some great pics of the early country and rockabilly artists from the 50s, and we hear clips of Patti Page’s “Tennessee Waltz,” Hank Williams’ “Cold, Cold Heart,” and Eddy Arnold’s “Bouquet of Roses.” And live-in-the-studio guests Glenn Canyon and the Americanyons serve up Kris Kristofferson’s “For the Good Times” alongside an original from the Canyon canon.

But most of what transpires in these 30 minutes feels as it felt when I took Dad’s class back when I attended the University of Cincinnati, including an interesting look at the development of BMI as a competing force with which ASCAP ended up having to reckon and five 1974-era prescient predictions about the future of country music, all of which, to one extent or another, have come true in the near-50 years since.

Please enjoy “Country Music II.” Episode 3 of Pop Music, U.S.A.

Not that there’s not some entertainment. No, we get an opening montage with Dad channeling Johnny Cash, complete with wig and hoisted-high guitar. And we get some great pics of the early country and rockabilly artists from the 50s, and we hear clips of Patti Page’s “Tennessee Waltz,” Hank Williams’ “Cold, Cold Heart,” and Eddy Arnold’s “Bouquet of Roses.” And live-in-the-studio guests Glenn Canyon and the Americanyons serve up Kris Kristofferson’s “For the Good Times” alongside an original from the Canyon canon.

But most of what transpires in these 30 minutes feels as it felt when I took Dad’s class back when I attended the University of Cincinnati, including an interesting look at the development of BMI as a competing force with which ASCAP ended up having to reckon and five 1974-era prescient predictions about the future of country music, all of which, to one extent or another, have come true in the near-50 years since.

Please enjoy “Country Music II.”

Not that there’s not some entertainment. No, we get an opening montage with Dad channeling Johnny Cash, complete with wig and hoisted-high guitar. And we get some great pics of the early country and rockabilly artists from the 50s, and we hear clips of Patti Page’s “Tennessee Waltz,” Hank Williams’ “Cold, Cold Heart,” and Eddy Arnold’s “Bouquet of Roses.” And live-in-the-studio guests Glenn Canyon and the Americanyons serve up Kris Kristofferson’s “For the Good Times” alongside an original from the Canyon canon.

But most of what transpires in these 30 minutes feels as it felt when I took Dad’s class back when I attended the University of Cincinnati, including an interesting look at the development of BMI as a competing force with which ASCAP ended up having to reckon and five 1974-era prescient predictions about the future of country music, all of which, to one extent or another, have come true in the near-50 years since.

Please enjoy “Country Music II.” Episode 2 of Pop Music, U.S.A.

Episode 2 of Dr. Simon Anderson’s Pop Music, U.S.A. covers the first of two looks at country music. (See previous blog posts for the context for this recent series of posts celebrating the 50th anniversary of Dad’s two music appreciation TV shows.) In Part I, we get the following:

- Dad’s look at the socio-cultural and psycho-emotional aspects of country music and how they differ from those of other genres–including prescient discussions of the suspicion with which Appalchia viewed the rest of the country, especially urban elites, that sound as if he’s commenting on today’s red- and blue-state divide

- a snippet of the bluegrass standard “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” at the beginning and a full-blown treatment of “Salty Dog Blues” (with some scintillating solo work from mandolin, flat-picked guitar, dobro, and banjo) at the end

- a full-length recording of Johnny Cash singing “Folsom Prison Blues” (with Carl Perkins, of “Blue Suede Shoes” fame, playing the guitar solo behind him)

- interesting examples of how juxtaposing genres sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t (Jimmie Rodgers skipping beats in a blues accompanied by Louis Armstrong and Earl “Fatha” Hines and then a delicious few seconds of what Dad’s bread-and-butter country example, “Born to Lose,” would sound like when ruined by the sophisticated jazz chords of a Duke Ellington ballad)

- haunting documentary pictures of Dust Bowl-era farmland and a testimony from an elderly couple who left Oklahoma for California during that time

- and a recording that is now part of Anderson family lore, Dad fulfilling his childhood dream of becoming a singing cowboy in the Gene Autry vein, complete with requisite attire (hat, chaps, guitar slung over his shoulder) and the ultimate example of cowboy love, planting a kiss on the nose of his horse.

Yes, this episode shows Dad at his Professor Harold Hill best. Thanks for your interest. I hope you enjoy “Country Music, Part I.”

Episode 1 of Pop Music, U.S.A.

Thanks to those who’ve read and watched the past several weeks’ worth of episodes of my father, Dr. Simon Anderson, for 40+ years a professor of music at the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music, and the first of his two distance-learning TV shows, Man and His Music. I posted video links to all 10 shows in previous blog posts in honor of the 50th anniversary of their airing on Cincinati’s PBS affiliate, WCET, TV-48, in the winter trimester (February, March, and early April) of 1973. The material from those shows eventually turned into his first textbook, The Musical Imperative, still published by the boutique publishing company he started out of our garage, Clifton Hills Press, now run by sister and brother-in-law out of Valparaiso, Indiana.

Because Man and His Music was such a hit (I remember with pride school friends coming up to me and saying, with a bit of awe in their voices, “I saw your dad on TV last night!”), and because Dad taught a very popular pop-music survey class in addition to his bread-and-butter offering, Music Appreciation, the powers that were at the university and PBS decided to do a sequel the following year based on the content that evetually became his second book. Both that text and the TV show were titled Pop Music, U.S.A. Rather than wait until next year, to celebrate an actual 50-year anniversary, I plan to post all 10 of the sequel shows while I’m on a roll.

Those who watched the Man and His Music episodes will find some of the presentations familiar, but both Dad and his producers upped the ante just a bit the second time around. For starters, Pop Music, U.S.A. features intro and outro montages like a real TV show, which took the production a step or two beyond basic cable-access fare. (Recognize the skytline from a similar shot used for the opening of WKRP?) That’s our family car in the intro, one of several Ford Country Squires (with the faux wood paneling) Dad owned during my childhood and adolescence. He’s sporting his signature fedora here as well, a constant sartorial accoutrement. Even though everybody and their uncle back seemed to smoke cigarettes, I was always aghast at the picture in the outro with the cigarette dangling from his lower lip. I remember asking myself in my spirit, “What price authenticity?” or a 10-year-old equivalent anyway.

The production values have improved just a bit in a year’s time, although they’re certainly laughable by today’s standards. What hasn’t changed in the new show is Dad’s insightful sociological and anthropological takes on why certain music evolves the way it does. His dissection of the three basic forms of pop songs–sentimental songs (of all styles: “I Don’t Know Why” in the same vein as “Light My Fire”), narrative songs, and humorous songs–is Dad in his element. It’s this kind of profound-but-accessible instruction–along with his willingness to be a song-and-dance man to get through to the I-dare-you-to-try-to-make-me-care-about-this-stuff students in the auditorium that was his typical classroom–that made him such a popular fixture at CCM for so long . . . and the primary reason why, for about 30 years, we rarely enjoyed a family dinner in a local restaurant without someone coming up to the table and thanking Dad for being a great teacher, often folks in their fifties reminiscing about their college experiences 30 years prior.

Episode 1 sets the stage for the episodes to follow, which will look at the four primary forms of popular music at that time, as Dad saw them: country, jazz, mainstream (including Broadway), and rock. Thanks for considering coming along for the ride over the next two or three months. Here’s the title episode, “Pop Music, U.S.A.”

Tenth and Final Episode of Man and His Music

Episode 10 of Man and His Music, “Historical Periods in Art Music II,” is Dad at his academic best. Pure scholars who might have rolled their eyes at some of Dad’s attempts to engage the engineers and accountants and nurses and, especially, D-I athletes in his classes with song-and-dance-man antics could broker no argument with this treatment of the traditional historical periods in art music. Indeed, Dad doesn’t touch popular music at all (as he did in the previous episode, showing how the periods apply to jazz as well as classical music) but nevertheless covers the material in interesting fashion, illustrating how “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” might have sounded in the Renaissance, in the Baroque Period, etc.

Accompanying him and bringing the concepts to musical life is a group of conservatory students who called themselves the Burnet Woods Wind Quintet. Burnet Woods was, and still is, a lovely park not too far from the University of Cincinnati’s main campus. At around the time of this recording, my mom would often take my siblings and me to play in the park, especially its long cement slide and paddleboats in the neighboring pond. For the Romantic Era offering, Dad joins the ensemble on the piano.

Accompanying him and bringing the concepts to musical life is a group of conservatory students who called themselves the Burnet Woods Wind Quintet. Burnet Woods was, and still is, a lovely park not too far from the University of Cincinnati’s main campus. At around the time of this recording, my mom would often take my siblings and me to play in the park, especially its long cement slide and paddleboats in the neighboring pond. For the Romantic Era offering, Dad joins the ensemble on the piano.

I’m stupid biased, of course, but I found myself LOLing a couple of times with the sweeping generalizations Dad makes here, the kinds of socio-cultural broad-brush painting that allowed his students to get a general sense of what was going on among the people, especially those whose exploits don’t usually get written up in history books. Throughout his whole career, Dad concerned himself more so than most scholars on the relevance of the vox populi, and that shows up in spades here. Dad gives one of my favorite music-history prof money lines in this lecture, while discussing the pendular swing of artistic expression between reason/control and passion/experimentation: “The seeds of greatness become the seeds of decay.” These are, of course, partly contrivances that meet pedagogical needs, and Dad acknowledges that early on, but in this episode it’s clear why Dad was such a favorite professor for 40 years of college students.

Next week, Lord willing, we’ll begin looking at his second show, this one more specifically focused on popular music, the appropriately titled Pop Music, U.S.A. Thanks again for those who are reading and watching these. I hope it’s almost as much fun for you as it is for me. Enjoy “Historical Periods in Art Music II.”

Busy Week at the Office; See You Next Week

Classes at Judson University start a week from yesterday, and I’m behind the 8-ball. We’ll resume the looks at Man and His Music next week, Lord willing.

Episode 9 of Man and His Music

I have argued throughout this series and in earlier blog posts that my father, Dr. Simon Anderson, during his 40+ years of teaching music at the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music, was way ahead of his time in lending legitimacy to popular music forms when the world of conservatory pedagody eschewed almost exclusively any musical art form that didn’t have its roots in western Europe and wasn’t at least 75 to 100 years old. In episode 9, “Historical Periods in Art Music I,” of his distance-learning collaboration with PBS’ Cincinnati affiliate, WCET, Man and His Music, Dad gives several examples of what was then pretty revolutionary music-classroom instruction.

First Dad provides four important caveats to art (and art music) history, understanding more effectively how the arts have been rendered throughout the past 500 years, which includes a populist notion of the pervasive nature of commissioned art and the effect-vs.-cause truths inherent in the epochal changes in stylistic directions we see in art history, with an aside to his favorite pop-cultural theorist, Marshall McLuhan, and the idea that the arts are the “antennae of the culture,” reflecting, much more so than driving, cultural change.

Then, after a look at how most professors cover music in the Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and Contemporary Periods (i.e, with examples from classical music only), Dad takes us through a quick look at what I feel is his most significant contribution to music appreciation, the fact that the same five categories we use for legit music can be applied to any form of popular music, such is the predictability of the ebb and flow of any artists’ responses to the pendular swinging between that which we can distiguish, to summarize simply, as the war between freedom and control. Hence, in what would have been fleshed out over the course of an entire lecture, we get a look at jazz music in each of the five periods normally reserved for the Three B’s (Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms); indeed, in other contexts Dad mentioned the Three B’s of jazz: Beiderbecke, Basie, and Brubeck.

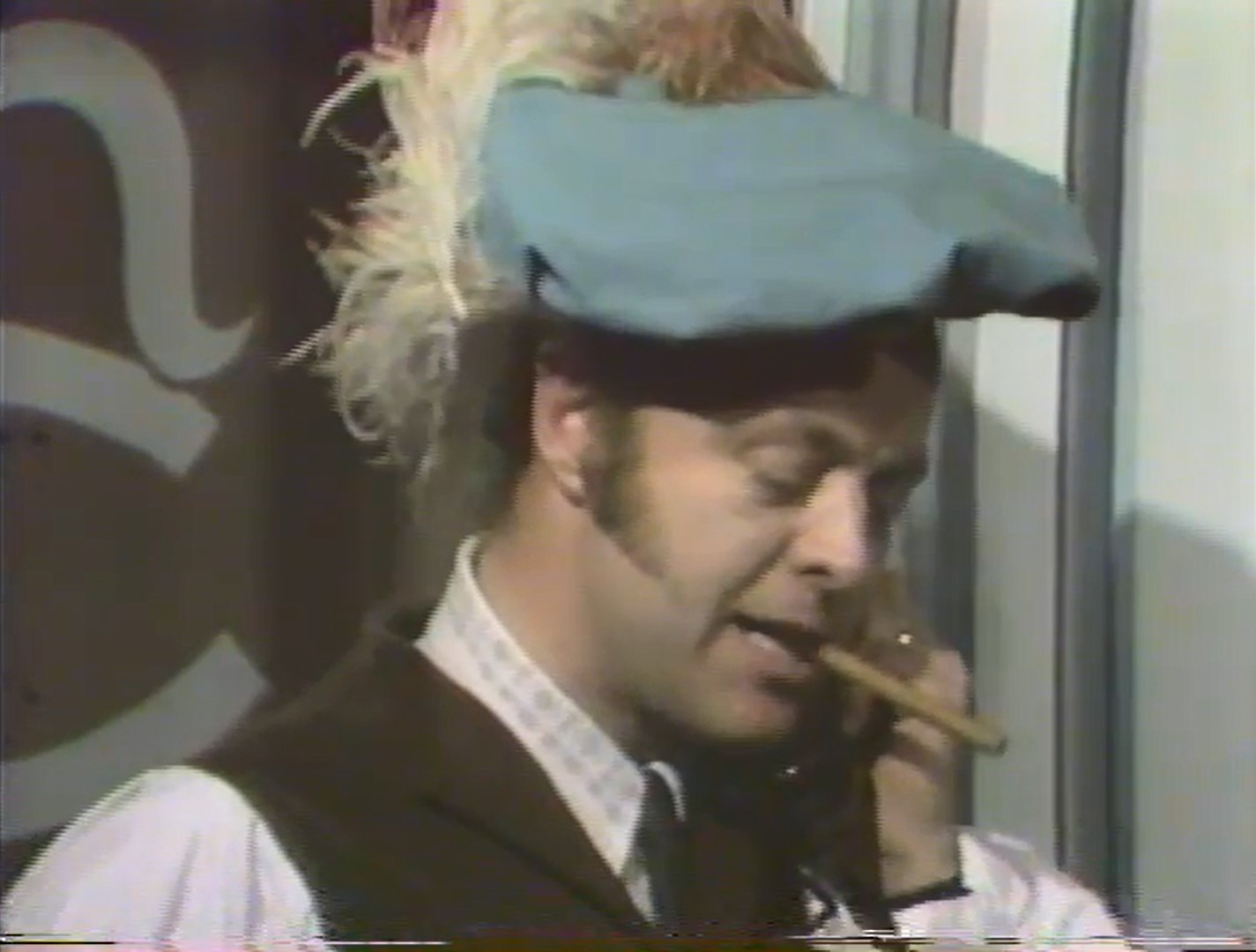

It’s hard all these years later to reflect accurately what a radical notion this was and how revolutionary such pedagogy was then, especially when Dad applied the exact same schema to the other forms of pop music, including country, Broadway, and rock (Elvis = Baroque, Hendrix = Romantic, etc.). All this acknowledged, Dad didn’t care about being right on this subject just for the sake of being right (although he didn’t waver in his belief that he had the proper view on all this). No, he still and always subscribed to the notion that part of being a great educator in the late 20th century traced a line back to Vaudeville entertainers. (To whatever extent that was true then, it’s self-evidently true 50 years later.) So along the way we get treated to a cool brass quintet and two sketches where Dad plays a cigar-chomping member of the ruling class placing a personal order to artists (Hadyn in one, Botticelli in the other) for commissioned art pieces. Never a dull moment when Dad was on stage . . . er, teaching.

It’s hard all these years later to reflect accurately what a radical notion this was and how revolutionary such pedagogy was then, especially when Dad applied the exact same schema to the other forms of pop music, including country, Broadway, and rock (Elvis = Baroque, Hendrix = Romantic, etc.). All this acknowledged, Dad didn’t care about being right on this subject just for the sake of being right (although he didn’t waver in his belief that he had the proper view on all this). No, he still and always subscribed to the notion that part of being a great educator in the late 20th century traced a line back to Vaudeville entertainers. (To whatever extent that was true then, it’s self-evidently true 50 years later.) So along the way we get treated to a cool brass quintet and two sketches where Dad plays a cigar-chomping member of the ruling class placing a personal order to artists (Hadyn in one, Botticelli in the other) for commissioned art pieces. Never a dull moment when Dad was on stage . . . er, teaching.

Hope you enjoy “Historical Periods in Art Music I.”

Episode 8 of Man and His Music

We see two hallmarks of Dad’s pedagogy in episode 8 of Man and His Music, “The Musical Stage.” First, as has been the case in all of the episodes thus far, Dad is all about bringing in others–sometimes colleagues, often students–to help illustrate his points, sure, but also to give others a chance to shine. As popular as Dad knew he was with his audiences, it wasn’t all about Simon and the opportunity to feed his own ego; it was–so, so often–about giving opportunities to folks to prove themselves in situations where they would stand a reasonable chance of being successful. So here we get a repeat visit from local Cincinnati TV personality Rob Reider, singing Kenny Rankin’s “Peaceful” early in the show and then an over-the-top and tongue-in-cheek rendition of a country weeper, “Ya Done Stomped on My Heart” near the end of the broadcast. We also hear from a couple of music theater conservatory students doing a duet from Pajama Game and a comedic musical troupe illustrating sketch-TV (Saturday Night Live was just two years away) musical renditions.

A personal case in point on this subject from my youth: As I became decent at jazz bass, Dad would use me on gigs periodically to keep the money in the family, when possible. Usually he did this in low-pressure situations where the spotlight wouldn’t burn too brightly (wedding receptions, bar mitzvahs), with friends of the family filling in the band (often a trio or quartet, so there were only one or two others playing with us). One time, however, he needed me at the last minute for a pretty high-visibility gig for some high rollers who had requested a sextet–i.e., there would be the likelihood of playing more complex pieces from the be-bop era as opposed to the Broadway show tunes we’d often do with a smaller group. As if that weren’t enough, as we pulled into the parking lot, Dad casually noted, “By the way, the trombonist on this gig just got off the road with the Woody Herman Band.” Good thing he hadn’t dropped this on me before we headed to the gig, or I’m sure I’d have been petrified and tempted to beg out.

Like the great educator he was, Dad called familiar tunes for the first hour or two, to allow me to get into a groove, but then, having facilitated my establishing myself as at least relatively competent to be on the same bandstand as these pros, he called a tune I’d never played. I gently leaned over to him and sheepishly said, “Dad, I’ve never played this one before.” As he did on countless occasions, he replied, “Watch closely, Small Bear,” an allusion to the father-son encouragement in the classic Berenstain Bears children’s books. Only after playing the tune through with a minimum of mistakes did I realize why he had positioned me right behind him, to the immediate left of the piano, within easy visible range of his left hand. For the duration of that song, and throughout good chunks of the rest of the gig, Dad, who didn’t need to play as much piano activity since there were three non-rhythm section musicians in the mix that night, took the index finger of his left hand and, a split second before the chord change, hovered it immediately over the correct note to play next. As long as I kept my eyes on that index finger, I was fine, and no one knew that I was WAY out of my league playing with these grizzled veterans.

Like the great educator he was, Dad called familiar tunes for the first hour or two, to allow me to get into a groove, but then, having facilitated my establishing myself as at least relatively competent to be on the same bandstand as these pros, he called a tune I’d never played. I gently leaned over to him and sheepishly said, “Dad, I’ve never played this one before.” As he did on countless occasions, he replied, “Watch closely, Small Bear,” an allusion to the father-son encouragement in the classic Berenstain Bears children’s books. Only after playing the tune through with a minimum of mistakes did I realize why he had positioned me right behind him, to the immediate left of the piano, within easy visible range of his left hand. For the duration of that song, and throughout good chunks of the rest of the gig, Dad, who didn’t need to play as much piano activity since there were three non-rhythm section musicians in the mix that night, took the index finger of his left hand and, a split second before the chord change, hovered it immediately over the correct note to play next. As long as I kept my eyes on that index finger, I was fine, and no one knew that I was WAY out of my league playing with these grizzled veterans.

The second hallmark on display in “The Musical Stage” is Simon the Showman, in full Professor Harold Hill mode. This shows up best in his parody of an opera ensemble piece following the evil baritone’s promise to the slit the throat of the voluptuous soprano for rejecting his advances. After first singing each of the solo parts (including the tenor’s off-in-the-wing “No, you won’t!” ascertation), Dad launches into the melody line from the chorus’ commentary: “And then the villagers come in, or the peasants come in from the hillside, or people come out of the taverns or through the doorways and around the trees and through the windows or out of the cigarette factory, and they sing,

Oh, watch him plunge that dagger into her lovely throat. She’ll bleed a bloody river; we’ll surely need a boat! Oh we’ll need a boat in Genoa tonight! We’ll need a boat in Genoa tonight!”

Around this time Dad was doing a lot of public speaking for various events, and sometimes he’d take me with him, partly to get me out of the house so Mom could put my two siblings to bed more easily, but partly because I think he sensed, even then, that I might follow in his pedagogical footsteps and would benefit from sitting at his feet when I could. On once such occasion, the topic was opera; Dad launched into “We’ll Need a Boat in Genoa,” and the audience roared. I must have been about 12 or so, and, to this day, I remember thinking my father was the coolest dad in the world and that I was so proud to be his son.

Hope you enjoy “The Musical Stage.”

Episode 7 of Man and His Music

Episode 7 of Man and His Music finds Dad exploring all kinds of choral forms, and we’re treated to a range of great choral music from a contemporary Black gospel choir, a barbershop quartet, and a collegiate madrigal singers ensemble, which performs Peter Schickele as P.D.Q. Bach’s send-up of traditional madrigals, “My Bonnie Lass She Smelleth.” (Note: The audio recorded features a lot of hiss and static. Back at the time these shows were recorded, you might have seen a scrolling message along the bottom of your TV feed saying something along the lines of “We are experiencing technical difficulties. The trouble is not in your set.” Consider this an equivalent notice.) I hope you enjoy “Choral Combinations.”

Episode 7 of Man and His Music finds Dad exploring all kinds of choral forms, and we’re treated to a range of great choral music from a contemporary Black gospel choir, a barbershop quartet, and a collegiate madrigal singers ensemble, which performs Peter Schickele as P.D.Q. Bach’s send-up of traditional madrigals, “My Bonnie Lass She Smelleth.” (Note: The audio recorded features a lot of hiss and static. Back at the time these shows were recorded, you might have seen a scrolling message along the bottom of your TV feed saying something along the lines of “We are experiencing technical difficulties. The trouble is not in your set.” Consider this an equivalent notice.) I hope you enjoy “Choral Combinations.”

Episode 6 of Man and His Music

For episode 6 of Man and His Music, “Vocal Styles,” Dad and his producers came up with the idea of casting the content in terms of a talk show, the likes of which were as popular then as they are now, if a bit less caffeinated. The model used was the shows of Mike Douglas or Merv Griffin, whereby guests engaged in serious dialogue on subjects from time to time and weren’t merely peddling their latest wares (movies, books, albums, etc.). Hence, the experience was often (not always) more intellectually stimulating than what we get today with the offerings from Kelly Ripa and less political than what we get from The View. Politics weren’t off limits–far from it–but they were discussed, by and large, respectfully and without the vitriol with which so much of our current political conversation is laced.

The host of the “show” here is Cincinnati media maven Rob Reider, who played the cheery sidekick to the older and more mature Bob Braun on the local daily noontime The Bob Braun Show. (George Clooney’s uncle, Nick, had a rival show that aired around the same time on a different local channel.) Reider had a marvelous singing voice, so his serving in this role would have made sense to Cincinnatians. He also fancied himself the comedian, which we see here throughout the episode. His continual mispronouncing of Dad’s name I’m pretty sure was an ad lib. Dad seems caught off guard initially but soon settles into the schtick and rolls with the punches like the pro he was. It would not have been unlike Reider to throw this into the mix at the last minute to spice things up a bit, and, in fact, it does add an edge to what would have started to become a bit predictable by the halfway point of the show.

Along the way, as always, we get great listening examples from the world of music to illuminate Dad’s content. After the farcical cold opening (hello, Saturday Night Live), in which a legit soprano incongruously intones Loggins & Messina’s “Your Mama Don’t Dance, and Your Daddy Don’t Rock ‘n’ Roll,” we settle into a catalog of vocal styles featuring the recorded likes of Sherrill Milnes, the English countertenor Alfred Deller, Bing Crosby, Ethel Merman, Ella Fitzgerald, Roy Acuff, Mick Jagger, and many more.

We also hear from University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music vocal students (one for each part, SATB) singing classical fare and illustrating various aspects of their abilities beyond the differences in their range. The slide-down-a-chair-to-allow-the-newest-guest-the-prime-real-estate efforts were a staple of these shows, particulary Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show (as opposed to many shows now, where the first guest does his/her thing and then exits, allowing the host to pay full attention to the next one). We also have some beautiful period fashion examples, vintage 70’s, including Reider’s bell-bottom slacks and every guy’s lapels. Quite the sartorial showcase.

We also hear from University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music vocal students (one for each part, SATB) singing classical fare and illustrating various aspects of their abilities beyond the differences in their range. The slide-down-a-chair-to-allow-the-newest-guest-the-prime-real-estate efforts were a staple of these shows, particulary Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show (as opposed to many shows now, where the first guest does his/her thing and then exits, allowing the host to pay full attention to the next one). We also have some beautiful period fashion examples, vintage 70’s, including Reider’s bell-bottom slacks and every guy’s lapels. Quite the sartorial showcase.

Thanks for reading. (Get more backstory, if interested, from previous posts.) Here’s Man and His Music, episode 6, “Vocal Styles.”

Episode 5 of Man and His Music

Episode 5 of Man and His Music, “Instrumental Forms,” covers material for which creative pedagogy is hard to come by. When you’re considering the structure of your basic piece of string quartet music, it is what it is what it is. Still, Dad brings some lightheartedness and fun to what would be, in the hands of most professors, a rather dull exercise. In this episode, for example, we get

Episode 5 of Man and His Music, “Instrumental Forms,” covers material for which creative pedagogy is hard to come by. When you’re considering the structure of your basic piece of string quartet music, it is what it is what it is. Still, Dad brings some lightheartedness and fun to what would be, in the hands of most professors, a rather dull exercise. In this episode, for example, we get

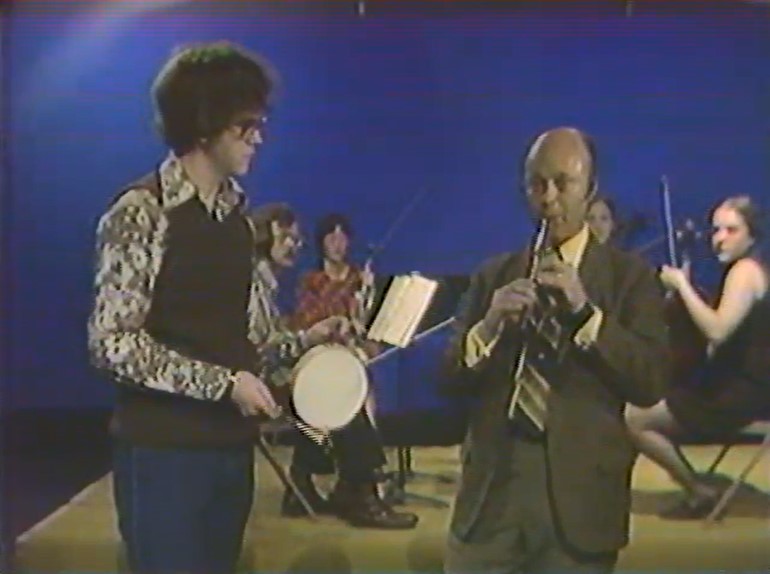

- Dad playing the recorder on two different versions of “Take Me out to the Ballgame,” one in duple (2/4) meter and one in triple (3/4) meter to illustrate Renaissance dance structures

- brief piano excerpts of “Sweet Sue,” “Tenderly,” and “How You Gonna Keep ‘Em down on the Farm” to illustrate disparate individual elements of a collective suite

- a lighthearted admission that there are too many different uses in classical music for the word sonata (“The trouble is the word sonata is used a half a dozen times in different ways, and you simply have to learn to thread your way through the labyrinth; there’s just no other way. Extrasensory Perception is what you need”)

- a bit of vocalese added to the primary themes of the first and fourth movement of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G minor: “Mozart’s in the closet (let him out, let him out, let him out)” and “It’s a bird, it’s a plane, no it’s Mozart!” respectively.

Along the way, of course, there is a lot of meat, and Dad, having entertained his students as best he possibly could given the material with which he was working, expected all those athletes, accountants, and engineers–who had been hoping for the easy A his classes were rumored to proffer–to muster up the self-discipline to sit respectfully through a legit musical offering when the time came (in this case, the entire fourth movement of a Haydn string quartet, nicely rendered by some conservatory students here).

Thanks for reading. I hope you enjoy Man and His Music, episode 5, “Instrumental Forms.”