I remember the incident as if it occured yesterday, though it’s been over 30 years, because of how profoundly it shaped the rest of my career. I was leading congregational singing for a Sunday night service at the church where I truly cut my teeth as a worship leader. I would have been 28 or 29 at the time, old enough to think more highly of myself than I ought, not old enough to have been humbled with any great regularity. We had a guest pastor that night, a gentleman who, not too long after this incident, became a good friend, someone I admire deeply. (In fact, when I became the chapel director at Judson University, I invited him to speak frequently.)

His sermon that night was titled “The Brush of Angels’ Wings. . .,” so I knew exactly what I was going to use as the table-setting song. Though this was a decade before I enrolled in the Robert E. Webber Institute for Worship Studies, where I learned the concept of Scripture-shaped worship (thank you, F. Russell Mitman), I was already keen to the idea that there should be a sense of flow in worship, and my job as a worship leader was to facilitate as seamless a transition as possible between the congregational singing and the message (and any other elements of the service; I was serving a good, low-church Baptist congregation, so we were two-fold all the way). Indeed, was there any possible choice other than Lanny Wolfe’s “Surely the Presence of the Lord Is in This Place”? For those born in the past 50 years, Wolfe was kind of a poor man’s Bill Gaither; both had a trio, and both wrote a lot of songs. To be fair, many of Wolfe’s were pretty good; I liked (and still like) his jazzy chords in “Surely.” Would that today’s cwm writers branched into some of Wolfe’s harmonic territory. (See the previous blog post.)

His sermon that night was titled “The Brush of Angels’ Wings. . .,” so I knew exactly what I was going to use as the table-setting song. Though this was a decade before I enrolled in the Robert E. Webber Institute for Worship Studies, where I learned the concept of Scripture-shaped worship (thank you, F. Russell Mitman), I was already keen to the idea that there should be a sense of flow in worship, and my job as a worship leader was to facilitate as seamless a transition as possible between the congregational singing and the message (and any other elements of the service; I was serving a good, low-church Baptist congregation, so we were two-fold all the way). Indeed, was there any possible choice other than Lanny Wolfe’s “Surely the Presence of the Lord Is in This Place”? For those born in the past 50 years, Wolfe was kind of a poor man’s Bill Gaither; both had a trio, and both wrote a lot of songs. To be fair, many of Wolfe’s were pretty good; I liked (and still like) his jazzy chords in “Surely.” Would that today’s cwm writers branched into some of Wolfe’s harmonic territory. (See the previous blog post.)

I can’t remember what other songs we sang that night, but when we came to “Surely,” and we got to the line that says, “I can hear the brush of angels’ wings, I see glory on each face,” I smiled inwardly. I had nailed it. “Isn’t our guest preacher going to appreciate how well I’ve paved the way for his message?” I mused to myself. Finishing up the last chorus (which had been preceded by a nice modulation from C to D-flat, I might add), singing the title line one final time, I closed in prayer, thanking God for His omnipresence in our lives, and made my way back to the soundboard, where I was recording the message for posterity. “Job well done,” I thought.

My contentment didn’t last long. Our guest began by listing several books that had recently been released, all of them touting New Age weirdness under the guise of Christian spirituality. These were not Christian mystics, embracing elements of historical and Orthodox Christian faith that, for however other-worldly the experiences, nevertheless pointed at all times to Christ. This was nutty stuff, and a segment of American Christianity at that time was buying it hook, line, and sinker. The preacher, rightly, exhorted Christians to eschew such fluff and banish it from our daily lives . . . every element . . . even, especially, our worship services . . . even, especially, our congregational singing. “And forgive me,” he said, “but I must say this because it illustrates the point. The song we just sang a minute ago. . . .”

I don’t remember much after that. I do recall slinking down behind the sound console as best I could, a rather forlorn hope for a guy my size. And I do recall, English major (two degrees) that I am, checking out the bulletin and seeing what I had obviously missed when I was doing my pre-service research: the question mark at the end. The sermon was actually titled “The Brush of Angels’ Wings. . .?” I had set the table for the speaker, all right, but with a negative example to prove his point.

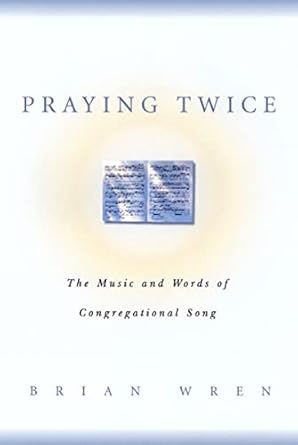

What’s the big deal? Two things, both related to the spiritually formative importance of the lyrics we sing in worship. There is mention of hearing the brush of the wings of living creatures in Scripture (Ezekiel 3:1-15), but it’s not a soothing sound. Far from it; there’s unsettling loud rumbling, and when the Spirit lifts Ezekiel away from this scene, he “went in bitterness” and anger–not the warm-fuzzy imagery Wolfe concocts for his song. Moreover, the title line alludes to Jacob’s encounter with the wrestling angel in Genesis 28 and Jacob’s pronouncement upon waking from his dream. But notice the tag: “Surely the Lord is in this place–and I didn’t know it!” (emphasis mine). Jacob sensed God’s presence only after the fact; he didn’t celebrate God’s being with him based on in-the-moment sensations. Jacob was walking by faith, not sight here; Wolfe’s lyrics celebrate sights that inspire faith. It’s a subtle but important difference, particulary where corporate worship is concerned, in a world that often clamors for the miraculous as a precursor (or, at best/worst, corequisite) to belief (Matt. 12:39). (I owe the second of these revelations to Brian Wren and his marvelous Praying Twice: The Music and Words of Congregational Song.)

What’s the big deal? Two things, both related to the spiritually formative importance of the lyrics we sing in worship. There is mention of hearing the brush of the wings of living creatures in Scripture (Ezekiel 3:1-15), but it’s not a soothing sound. Far from it; there’s unsettling loud rumbling, and when the Spirit lifts Ezekiel away from this scene, he “went in bitterness” and anger–not the warm-fuzzy imagery Wolfe concocts for his song. Moreover, the title line alludes to Jacob’s encounter with the wrestling angel in Genesis 28 and Jacob’s pronouncement upon waking from his dream. But notice the tag: “Surely the Lord is in this place–and I didn’t know it!” (emphasis mine). Jacob sensed God’s presence only after the fact; he didn’t celebrate God’s being with him based on in-the-moment sensations. Jacob was walking by faith, not sight here; Wolfe’s lyrics celebrate sights that inspire faith. It’s a subtle but important difference, particulary where corporate worship is concerned, in a world that often clamors for the miraculous as a precursor (or, at best/worst, corequisite) to belief (Matt. 12:39). (I owe the second of these revelations to Brian Wren and his marvelous Praying Twice: The Music and Words of Congregational Song.)

Worship leaders, we have the sacred privilege of selecting the words our congregations will sing in praise to Almighty Triune God. Choose wisely.

The Lord be with you!

I have been using the late Walter Wangerin’s Advent collection,

I have been using the late Walter Wangerin’s Advent collection,  I’d like the passage to 60 to go more smoothly, so I’m gearing up for it more intentionally. As I thought about how to get through the next week and a half relatively unscathed, I was reminded of some guidance I had received from an old friend in the midst of grieving my dad’s death. My relationship with singer/songwriter Leonard Cohen was, to be sure, one-sided (we never met), and it came on rather late in his life; as was the case with Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, and all the old gutbucket African-American bluesmen from the 1920s-1940s, I couldn’t, in my bel canto snobbery, get past Cohen’s vocal quality, or lack thereof, completely missing the McLuhanesque truth that his tonal quality is, in many ways, his message. When I finally subjected Cohen to the same deep-dive I had given Dylan 15 years earlier, I rose from those waters a convert.

I’d like the passage to 60 to go more smoothly, so I’m gearing up for it more intentionally. As I thought about how to get through the next week and a half relatively unscathed, I was reminded of some guidance I had received from an old friend in the midst of grieving my dad’s death. My relationship with singer/songwriter Leonard Cohen was, to be sure, one-sided (we never met), and it came on rather late in his life; as was the case with Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, and all the old gutbucket African-American bluesmen from the 1920s-1940s, I couldn’t, in my bel canto snobbery, get past Cohen’s vocal quality, or lack thereof, completely missing the McLuhanesque truth that his tonal quality is, in many ways, his message. When I finally subjected Cohen to the same deep-dive I had given Dylan 15 years earlier, I rose from those waters a convert.  To illustrate the latter, Dad shows a clip of the early 70s Nashville sessions featuring the (perceived) conservative Johnny Cash and the (perceived) liberal (Bob Dylan), captured here singing Dylan’s “One Too Many Mornings.” (History has shown that, in truth, neither artist was as beholden to the political poles as had been assumed, the clues for which were there if anyone wanted to look for them.) We also hear some excellent voice-over commentary from the fabulous bluegrass banjoist Earl Scruggs, extolling the virtues of trying out new ideas, while his new band, featuring his sons on various instruments not usually associated with bluegrass, plays a rollicking “newgrass” tune in the background. I hope you enjoy this

To illustrate the latter, Dad shows a clip of the early 70s Nashville sessions featuring the (perceived) conservative Johnny Cash and the (perceived) liberal (Bob Dylan), captured here singing Dylan’s “One Too Many Mornings.” (History has shown that, in truth, neither artist was as beholden to the political poles as had been assumed, the clues for which were there if anyone wanted to look for them.) We also hear some excellent voice-over commentary from the fabulous bluegrass banjoist Earl Scruggs, extolling the virtues of trying out new ideas, while his new band, featuring his sons on various instruments not usually associated with bluegrass, plays a rollicking “newgrass” tune in the background. I hope you enjoy this

Having covered an introduction to pop music, country music, and jazz in the first five episodes, Dad now turns his attention to what he calls mainstream pop, middle-of-the-road fare that encompasses everything from Vaudeville to Broadway. After the Tonight Show-esque cold opening, in which he plays a fierecely heckled Vaudeville perfomer, he begins the meat of the show by articulating five traits of successful mainstream peformers and then moves into some of his bread-and-butter analysis of the socio-economic factors at work that make the creation of West Side Story, for example, impossible to conceive as a story set in Nebraska. This was Dad’s forte, creating sweeping generalizations that helped students get a handle on the huge world of music. Later he accompanies on the piano two vocal grad students who sing examples of Broadway tunes, “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” from Porgy and Bess, and “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” from Showboat.

Having covered an introduction to pop music, country music, and jazz in the first five episodes, Dad now turns his attention to what he calls mainstream pop, middle-of-the-road fare that encompasses everything from Vaudeville to Broadway. After the Tonight Show-esque cold opening, in which he plays a fierecely heckled Vaudeville perfomer, he begins the meat of the show by articulating five traits of successful mainstream peformers and then moves into some of his bread-and-butter analysis of the socio-economic factors at work that make the creation of West Side Story, for example, impossible to conceive as a story set in Nebraska. This was Dad’s forte, creating sweeping generalizations that helped students get a handle on the huge world of music. Later he accompanies on the piano two vocal grad students who sing examples of Broadway tunes, “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” from Porgy and Bess, and “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” from Showboat.