This is post number nine in a series of random reflections I have been amassing over the past couple of years since retiring from steady, local-church, “weekend warrior” worship ministry. These ruminations are in no particular order, and they vary in significance. I welcome discussion on any of them.

Reflection #9: The “overwhelming, never-ending” I-IV-V-vi harmonic structure of so many contemporary worship songs underserves a Church whose Subject and Object of worship is the Creator of the infinitely diverse universe.

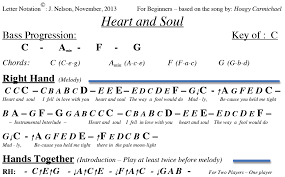

Hang around musical children for any length of time, and you will eventually hear two of them at the piano playing the two parts of “Heart and Soul.” They will play, without apparent fatigue (and without adding the virtually unknown bridge, which would help to alleviate the water-torture-like repetition), for a long time. They will switch parts. They will play in different octaves. But they will pound out the same basic patterns until most adults in the room want to scream, “PLEASE PLAY SOMETHING ELSE!” (If you’ve only heard kids render this song, here’s what it sounds like in its original context: “Heart and Soul.”)

Hang around musical children for any length of time, and you will eventually hear two of them at the piano playing the two parts of “Heart and Soul.” They will play, without apparent fatigue (and without adding the virtually unknown bridge, which would help to alleviate the water-torture-like repetition), for a long time. They will switch parts. They will play in different octaves. But they will pound out the same basic patterns until most adults in the room want to scream, “PLEASE PLAY SOMETHING ELSE!” (If you’ve only heard kids render this song, here’s what it sounds like in its original context: “Heart and Soul.”)

I often feel this way whenever I listen to extended doses of contemporary worship music these days. The same chords (uppercase Roman numerals = major chords; lowercase = minor) used in “Heart and Soul”–I, iv, IV, and V (the tonic, submediant, subdominant, and dominant, respectively, in music-theory-speak)–show up in alarming regularity in contemporary worship. Oh, they get mixed around a bit, to be sure. Sometimes it’s I-IV-vi-V (the beginning of “What a Beautiful Name”); other times it’s IV-I-V-vi (both the verses and choruses of “10,000 Reasons”); and sometimes it’s vi, V, IV, I (the chorus of “King of My Heart”). But those four chords reign supreme.

Sometimes exclusively, I’m afraid. Yesterday afternoon I printed out the chord charts for the Top 20 current contemporary worship songs, as tracked by CCLI (CCLI Top 20). Here’s what I discovered:

- 10 of the Top 20 use the I, IV, V, and vi chords exclusively

- 5 of the Top 20 add a ii chord (supertonic) for a total of five chords

- 2 of the Top 20 add a iii chord (mediant) for a total of five chords

- 2 of the Top 20 add a ii chord but drop the V chord, an interesting touch, for a total of four chords

- Only 1 of the Top 20 (“Revelation Song”) ventures into out-of-the-ordinary territory, utilizing the rarely heard v chord and the flat-VII (subtonic)–no V and no vi–but this excellent change of pace is muted by the use of the same exact I-v-bVII-IV pattern, with no variation, for both the verses and the choruses. (A similarly daring song, harmonically speaking, “Worship the Great I AM,” with its I-bIII-bVII-IV structure, also uses the same four chords, in the same order, for both verses and choruses.)

My little research project didn’t factor in tiny differences like suspended chords, chords with a major or minor seventh, or chords with the third or the fifth in the bass–nor did I consider introductions or instrumental interludes, which occasionally deviate harmonically from the the rest of the song (like “In Christ Alone,” with its v chord, which opens both the introduction and the instrumental interlude). That acknowledged, I would argue that contemporary worship music needs to break out of its harmonic rut.

“What’s the big deal?” some might ask. God is being glorified. The Church is worshiping, it can be argued, more passionately than it has in years. How can that be wrong or bad? It’s not, necessarily–but it’s also not evidence of worship musicians studying to show themselves approved (2 Tim. 2:15) where the craft of songwriting is concerned. While I don’t wish to make Rory Noland and Greg Ferguson’s harmonically rich and satisfying “He Is Able” (with its nine different chords!) the standard, and I don’t expect every songwriter to be able to pull off the wildly inventive harmonic structure Jason Ingram, Reuben Morgan, and Stuart Garrard achieved in the first two verses of “The Greatness of Our God,” I am calling for better craftsmanship, as a general rule, in contemporary worship music, especially re: harmonic structure. If you are a writer of the Church’s songs, let me offer two quick and easy ways for you immediately to improve your efforts.

First, study the masters–and I don’t mean Chris Tomlin and Matt Redman, as much as I  often appreciate their music. You can do a lot worse, for example, than listening to a steady diet of The Beatles. Put their two greatest hits collections–1962-1966 (the “Red Album”) and 1967-1970 (the “Blue Album”)–on regular rotation for a couple of weeks, and see if feasting on Lennon/McCartney songs (both eminently singable and stunningly diverse, harmonically speaking) doesn’t open up pathways of creativity for you that have previously been untapped. Paul Simon, especially of late, would be another. Joni Mitchell is a third. These are pop music’s Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms. Why would you not want to study them?

often appreciate their music. You can do a lot worse, for example, than listening to a steady diet of The Beatles. Put their two greatest hits collections–1962-1966 (the “Red Album”) and 1967-1970 (the “Blue Album”)–on regular rotation for a couple of weeks, and see if feasting on Lennon/McCartney songs (both eminently singable and stunningly diverse, harmonically speaking) doesn’t open up pathways of creativity for you that have previously been untapped. Paul Simon, especially of late, would be another. Joni Mitchell is a third. These are pop music’s Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms. Why would you not want to study them?

Second, at least for a month or two, don’t allow yourself to write anything that falls back on the I-IV-V-vi patterns. Use iii chords, flat-VI or flat-VII chords, or iv chords–anything but the usual. Just do it.

The Lord be with you, especially you songwriters, as you seek to honor Him with your best efforts! The Creator of the infinitely diverse universe deserves no less.

Coming next week (Lord willing): Worship budgets.

the sartorially splendid Dr. Tony Evans, Dallas’ Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship). Pure and simple, this was the expectation, and it crossed all denominational lines.

the sartorially splendid Dr. Tony Evans, Dallas’ Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship). Pure and simple, this was the expectation, and it crossed all denominational lines. Any pastor who dressed as casually as most evangelical pastors do today (represented here by Andy Stanley, suburban Atlanta’s North Point Community Church) would have faced scrutiny from an elder board, a worship committee, or a pastor-parish council.

Any pastor who dressed as casually as most evangelical pastors do today (represented here by Andy Stanley, suburban Atlanta’s North Point Community Church) would have faced scrutiny from an elder board, a worship committee, or a pastor-parish council. (represented here by Brian Tome, Cincinnati’s Crossroads Church) would have faced discipline from an elder board, a worship committee, and a pastor-parish council.

(represented here by Brian Tome, Cincinnati’s Crossroads Church) would have faced discipline from an elder board, a worship committee, and a pastor-parish council. ever heard. I once calculated the number of chapel services I attended in my 22 years as the driving staff force behind Judson’s chapels: just shy of 2,000. I can’t recall details of most of them, but I remember Evans’ words 20 years and 1,000 chapels later. (The gist of his message on the will of God focused on the intersection of God’s gifts and our passions.)

ever heard. I once calculated the number of chapel services I attended in my 22 years as the driving staff force behind Judson’s chapels: just shy of 2,000. I can’t recall details of most of them, but I remember Evans’ words 20 years and 1,000 chapels later. (The gist of his message on the will of God focused on the intersection of God’s gifts and our passions.) The thought comes from Andy Crouch, itinerant speaker and author of a slew of books, including Playing God: Redeeming the Gift of Power. My wife and I have of late found Crouch’s words to be prophetic for our times. I commend his entire Q talk (

The thought comes from Andy Crouch, itinerant speaker and author of a slew of books, including Playing God: Redeeming the Gift of Power. My wife and I have of late found Crouch’s words to be prophetic for our times. I commend his entire Q talk ( The prayer comes from a collection of Puritan prayers entitled The Valley of Vision that I have used in my devotional efforts the past couple of years. I pray this prayer, “The Cry of a Convicted Sinner,” on behalf of those in leadership at Willow Creek who have caused their brothers and sisters grief and pain, but even more so I pray this for myself (for though my sins might not make front-page news, they are as vile as anyone’s), and I would encourage you to do the same (for though your sins might not shake to the core an institution that has had 40 years of global impact, they are as reprehensible as anybody’s).

The prayer comes from a collection of Puritan prayers entitled The Valley of Vision that I have used in my devotional efforts the past couple of years. I pray this prayer, “The Cry of a Convicted Sinner,” on behalf of those in leadership at Willow Creek who have caused their brothers and sisters grief and pain, but even more so I pray this for myself (for though my sins might not make front-page news, they are as vile as anyone’s), and I would encourage you to do the same (for though your sins might not shake to the core an institution that has had 40 years of global impact, they are as reprehensible as anybody’s). enhanced by an understanding of some basic but important principles of communication. One of those classes is a 400-level Communication Theory class taught by my colleague Dr. Brenda Buckley-Hughes. Typically, halfway through the semester, students’ heads are swimming; by the end of the semester, most of those students have become equipped to bring a deeper understanding of what worship leaders can (and, we would argue, should) bring to corporate worship. It’s amazing to see.

enhanced by an understanding of some basic but important principles of communication. One of those classes is a 400-level Communication Theory class taught by my colleague Dr. Brenda Buckley-Hughes. Typically, halfway through the semester, students’ heads are swimming; by the end of the semester, most of those students have become equipped to bring a deeper understanding of what worship leaders can (and, we would argue, should) bring to corporate worship. It’s amazing to see. wealth of information; their customer-support people are also extremely helpful. CCLI isn’t the only licensing agency that covers churches, but it is Windows to everyone else’s Linux. Some “liturgical churches” (see the post from a few weeks back) use

wealth of information; their customer-support people are also extremely helpful. CCLI isn’t the only licensing agency that covers churches, but it is Windows to everyone else’s Linux. Some “liturgical churches” (see the post from a few weeks back) use  only. Many churches, technically, in order to be completely copyright compliant, given the way they use music and/or video in their ministries, need to purchase at least another license or two. (A really quick and dirty reference guide can be found here:

only. Many churches, technically, in order to be completely copyright compliant, given the way they use music and/or video in their ministries, need to purchase at least another license or two. (A really quick and dirty reference guide can be found here:  Dr. Constance Cherry, from whose modern-day classic, The Worship Architect, I borrow liberally for this blog. All three of the books in her Architect series, which includes The Special Service Worship Architect and The Music Architect, are must-reads for worship leaders.

Dr. Constance Cherry, from whose modern-day classic, The Worship Architect, I borrow liberally for this blog. All three of the books in her Architect series, which includes The Special Service Worship Architect and The Music Architect, are must-reads for worship leaders. worship, as contemporary worship leader/liturgist Aaron Niequist attests:

worship, as contemporary worship leader/liturgist Aaron Niequist attests:  [in worship]”; hence, as my Judson University colleague Mark Torgerson likes to point out, all churches are liturgical. But in the culture of the contemporary American church, historically “liturgical” churches tend to utilize tools such as creeds, responsive readings, corporate confessions, times of silence, and weekly observance of the Eucharist (or communion or the Lord’s Table/Supper). Historically “non-liturgical” churches tend to eschew these activities–except for communion (very rarely “the Eucharist”), which is observed monthly, quarterly, or even annually. “Liturgical” churches are often referred to via the adjective “high-church,” and “non-liturgical” churches are often referred to via the adjective “low-church.” (I’m going to abandon the quotation marks henceforth, but please understand them to be there in spirit.)

[in worship]”; hence, as my Judson University colleague Mark Torgerson likes to point out, all churches are liturgical. But in the culture of the contemporary American church, historically “liturgical” churches tend to utilize tools such as creeds, responsive readings, corporate confessions, times of silence, and weekly observance of the Eucharist (or communion or the Lord’s Table/Supper). Historically “non-liturgical” churches tend to eschew these activities–except for communion (very rarely “the Eucharist”), which is observed monthly, quarterly, or even annually. “Liturgical” churches are often referred to via the adjective “high-church,” and “non-liturgical” churches are often referred to via the adjective “low-church.” (I’m going to abandon the quotation marks henceforth, but please understand them to be there in spirit.) Last week my wife and I attended a gathering of members of the community of the Robert E. Webber Institute for Worship Studies (Jacksonville, Fla.), where I did my doctoral work in worship. Seated round the table were administrators, alumni, and prospective students, one of whom was a 25-year-old former worship arts student of mine at Judson University who is contemplating pursuing a master’s in worship at IWS. Among the topics of discussion was the notion, confirmed by my former student, that millennials and members of Gen Z are not turned off by liturgical practices anywhere near to the extent that many of their parents’ generation seemed to be–that, in fact, many long for something more substantive in worship, and many seem to find more substance in liturgy.

Last week my wife and I attended a gathering of members of the community of the Robert E. Webber Institute for Worship Studies (Jacksonville, Fla.), where I did my doctoral work in worship. Seated round the table were administrators, alumni, and prospective students, one of whom was a 25-year-old former worship arts student of mine at Judson University who is contemplating pursuing a master’s in worship at IWS. Among the topics of discussion was the notion, confirmed by my former student, that millennials and members of Gen Z are not turned off by liturgical practices anywhere near to the extent that many of their parents’ generation seemed to be–that, in fact, many long for something more substantive in worship, and many seem to find more substance in liturgy. be readily apparent for those who have never experienced them before. I look forward to seeing how all of this plays out in the years to come; in the meantime, if the exploration of anything above appeals to you, consider picking up a copy of Aaron Niequist’s forthcoming new book, The Eternal Current: How a Practice-Based Faith Can Save Us from Drowning.

be readily apparent for those who have never experienced them before. I look forward to seeing how all of this plays out in the years to come; in the meantime, if the exploration of anything above appeals to you, consider picking up a copy of Aaron Niequist’s forthcoming new book, The Eternal Current: How a Practice-Based Faith Can Save Us from Drowning. I suppose I could put “As a general rule” in front of all of these reflections, as there will always be examples where the complete opposite is true, but the introductory qualifying phrase is more appropriate than usual here. I recognize there is so much room for improvement where diversity on the typical American church platform is concerned. Dr. King’s assertion that 11 a.m. on Sunday morning is the most-segregated hour of the week is still, unfortunately, true.

I suppose I could put “As a general rule” in front of all of these reflections, as there will always be examples where the complete opposite is true, but the introductory qualifying phrase is more appropriate than usual here. I recognize there is so much room for improvement where diversity on the typical American church platform is concerned. Dr. King’s assertion that 11 a.m. on Sunday morning is the most-segregated hour of the week is still, unfortunately, true. serves well as a conclusion to these thoughts:

serves well as a conclusion to these thoughts: P.S. Re: last week’s post, the best resource I’ve come across to help worship leaders find words for worship is the aptly named Worship Words, by Debra and Ron Rienstra. Highly recommended!

P.S. Re: last week’s post, the best resource I’ve come across to help worship leaders find words for worship is the aptly named Worship Words, by Debra and Ron Rienstra. Highly recommended! I am, of course, biased. My JU colleagues and I worked long and hard 20 years ago coming up with a worship arts curriculum that wasn’t just a music-performance degree with one or two worship-related courses sprinkled on top. We offer unique courses like Speaking the Faith (a communication-arts approach to the non-musical skills required of worship leaders) and Worship and the Arts (a theology of all the arts, not just music, that combines theory and practice), and we make our students pursuing a Praise and Worship Music minor take a class called The History of Rock and Roll: The Medium and Its Message, for reasons that should be obvious to anyone who has attended a church utilizing contemporary worship music.

I am, of course, biased. My JU colleagues and I worked long and hard 20 years ago coming up with a worship arts curriculum that wasn’t just a music-performance degree with one or two worship-related courses sprinkled on top. We offer unique courses like Speaking the Faith (a communication-arts approach to the non-musical skills required of worship leaders) and Worship and the Arts (a theology of all the arts, not just music, that combines theory and practice), and we make our students pursuing a Praise and Worship Music minor take a class called The History of Rock and Roll: The Medium and Its Message, for reasons that should be obvious to anyone who has attended a church utilizing contemporary worship music. Dr. Rory Noland wrote a beautiful article on this subject in Worship Leader magazine recently. I encourage you to read the whole article here (

Dr. Rory Noland wrote a beautiful article on this subject in Worship Leader magazine recently. I encourage you to read the whole article here ( Point out interesting sights along the way that might not be obvious to all of us. The time when we could assume a basic biblical literacy in our congregations is long gone. Even concepts that seem painfully apparent to you might benefit from attention. For example, if you’re singing “This Is Amazing Grace,” consider taking a moment to give a basic definition of grace, reading a brief excerpt from either of Philip Yancey’s books on the subject, or quoting (and briefly explaining) 2 Cor. 12:7b-10. As a worship tour guide, don’t assume the congregation will necessarily know what to look for–or even how to recognize it when they see it.

Point out interesting sights along the way that might not be obvious to all of us. The time when we could assume a basic biblical literacy in our congregations is long gone. Even concepts that seem painfully apparent to you might benefit from attention. For example, if you’re singing “This Is Amazing Grace,” consider taking a moment to give a basic definition of grace, reading a brief excerpt from either of Philip Yancey’s books on the subject, or quoting (and briefly explaining) 2 Cor. 12:7b-10. As a worship tour guide, don’t assume the congregation will necessarily know what to look for–or even how to recognize it when they see it. (As a side note, I generally am of the opinion that the words in quotation marks above are inadequate for serious reflection of worship music. For a discussion of alternative terms and structures that can enrich our vocabulary in conversations on this topic, I recommend an essay, “A Rose by Any Other Name,” written by one of my first grad-school worship profs, Dr. Lester Ruth [

(As a side note, I generally am of the opinion that the words in quotation marks above are inadequate for serious reflection of worship music. For a discussion of alternative terms and structures that can enrich our vocabulary in conversations on this topic, I recommend an essay, “A Rose by Any Other Name,” written by one of my first grad-school worship profs, Dr. Lester Ruth [

the congregation at some point in the regular worship gatherings of the Church to sing what at Judson University’s Demoss Center for Worship in the Performing Arts we call “the soundtrack of your faith,” that music that was integral to and/or utilized by the Church at the time of your conversion. Because of all that has been discussed above, this task is easier now for worship leaders than ever before, but some effort will still be required, especially for younger worship leaders who weren’t around at the dawn of cwm, to broaden the worship set list beyond whatever Bethel and Hillsong United have released in the past five years.

the congregation at some point in the regular worship gatherings of the Church to sing what at Judson University’s Demoss Center for Worship in the Performing Arts we call “the soundtrack of your faith,” that music that was integral to and/or utilized by the Church at the time of your conversion. Because of all that has been discussed above, this task is easier now for worship leaders than ever before, but some effort will still be required, especially for younger worship leaders who weren’t around at the dawn of cwm, to broaden the worship set list beyond whatever Bethel and Hillsong United have released in the past five years.